By Sophie Grosserode

Students at The Windward School in White Plains and Harrison are using their brains to advance research on how to improve reading instruction — but not in the way you might think.

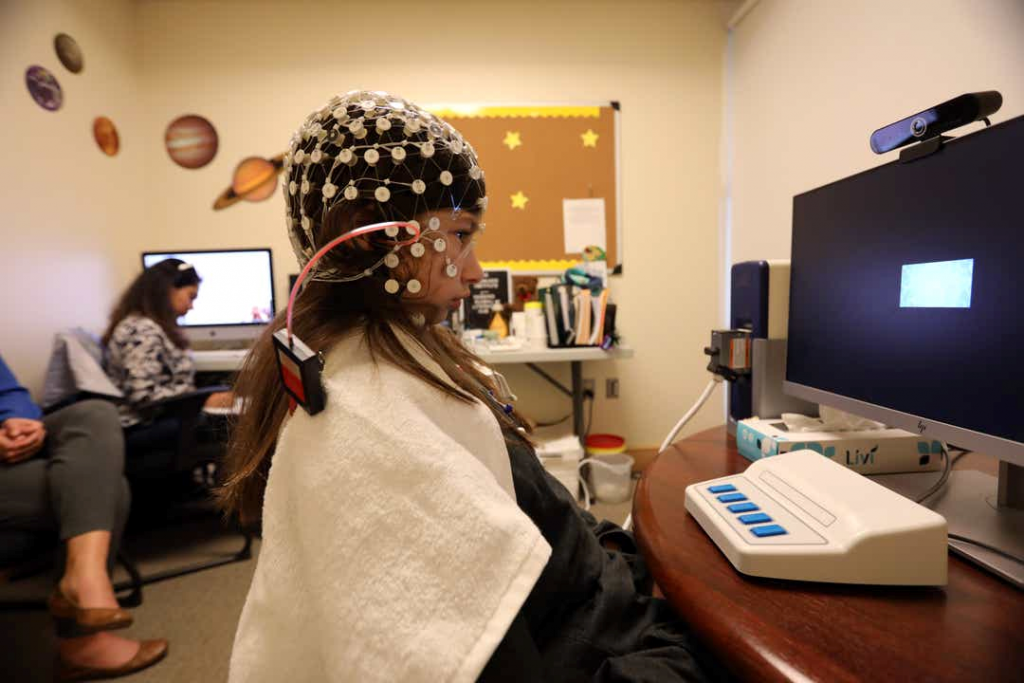

Twenty-two students in grades 1 to 6 are having their brains imaged by researchers. The kids are putting on snug-fitting caps, like hairnets, which hold electrodes that capture brain signals. That way, researchers can track changes in students’ brain activity while they read.

The goal is to show that Windward’s methods don’t only change a child’s test scores. They change a child’s brain. Then educators can use the results to fine-tune their instruction.

Tania Savayan/The Journal News “If you have indigestion or heartburn, and it gets better over time in response to treatment, then you know that something must have changed in your gut to produce this positive outcome,” said Nicole Landi, director of EEG research at Haskins Laboratories, which is partnering with Windward on the project. “When we see changes in behaviors that are significant over time, we can see these changes in our neural measures.”

Windward is an independent school, with campuses in White Plains, West Harrison and Manhattan, for students with language-based learning disabilities like dyslexia. The school is well known for its rigorous emphasis on phonics instruction, which teaches kids which sounds go with which letters and how those sounds make words.

“We have a tremendous amount of data that would show that the phonics-based approach is absolutely the best way to do this,” said Jamie Williamson, Windward’s head of school. He was referring to all reading instruction, but especially for dyslexic students struggling to read.

Now the school is expanding into neuroscience to unlock new information about the effects of reading instruction. The Windward Institute, a new arm of the school that manages external partnerships, announced in February that it was partnering with Haskins Laboratories in a project that would join researchers and educators.

Haskins describes itself as an independent community of researchers from a variety of fields who study language. It is affiliated with Yale and the University of Connecticut.

The students participating in the study were all new to Windward, so that researchers could look at their brains “pre-intervention” and then monitor them periodically during their normal instruction at the school, said Annie Stutzman, assistant director of The Windward Institute.

The first round of research this fall is being administered by a postdoctoral researcher, but teachers are being trained to administer electroencephalogram, or EEG, caps themselves come spring, while Haskins researchers supervise. The study is scheduled to go on for at least three years.

“Eventually, we should be able to run this ourselves in-house, which is really exciting for us,” Stutzman said.

So far, the student subjects have been enthralled with the science of their own brains, said John J. Russell, executive director of The Windward Institute. They can see the changes in their EEG when they blink or grit their teeth. “Several of our parents said the children came home and said, ‘Can I do that again tomorrow?’ ” Russell said.

Measuring changes in the brain

Landi said researchers are looking at “event-related potentials” or ERPs, which are measures of the brain’s response to specific stimuli. By presenting the same children with the same stimuli over time, they can measure tiny changes in ERPs.

First they measure a child’s brain activity in a “resting state,” while the child sits. Then the child completes four tasks, from reading words and listening to isolated sounds to watching movie clips and listening to longer story passages.

All the while, electrodes are transmitting electrical information to a computer so Haskins researchers can measure how the child’s brain is responding to each task. The whole thing takes about 90 minutes.

One hope of Windward officials is to learn something about the 2% of students who do not respond to the school’s instructional techniques, known in the literature as “resistors.” Perhaps they can develop interventions to help them.

“We get great results,” Russell said. “But can we do a better job of identifying which specific instructional strategies work best for which child?”

Everyone involved in the the project hopes that their findings will eventually have applications beyond Windward and instruction for students with learning disabilities. Their work could assist the development of individualized instructional programs, based in neurobiology, that benefit all students learning to read.

“Kids really love it,” Landi said. “Them being able to see that we can measure this stuff, and that is actually telling us something about their brain, and that we’re going to learn about how to help other kids read, I think they get really excited.”