A filmmaker who grew up with dyslexia advocates for an enlightened, compassionate educational approach.

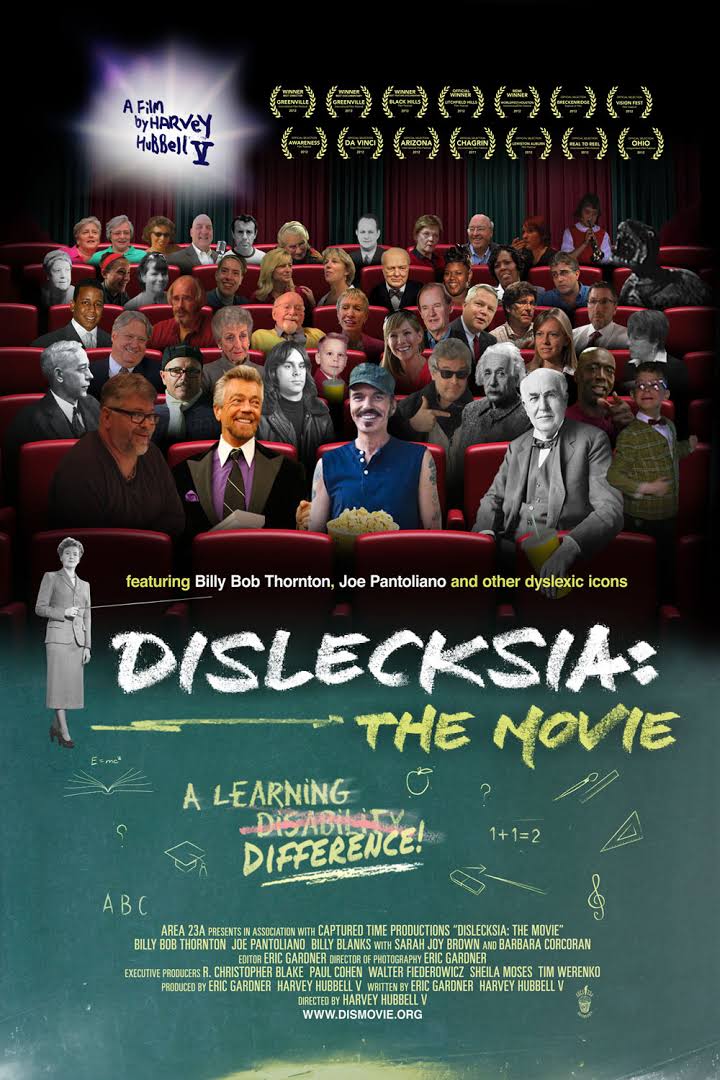

Growing up in the 1960s, filmmaker Harvey Hubbell V struggled with what was labeled a “perception problem,” and it made school a drag. His upbeat documentary Dislecksia: The Movie traces breakthroughs in the understanding and treatment of dyslexia, emphasizing that it’s a “learning difference” and not a disorder — and one that affects as many as 35 million Americans. Playful and at times self-indulgent, Hubbell’s film is a work of advocacy journalism that aims to inspire parents and educators. After bowing in New York (Oct. 4) and Los Angeles (Oct. 11), it’s scheduled for nationwide screenings on Oct. 17, some with Q&As, in conjunction with National Dyslexia Awareness Month.

Growing up in the 1960s, filmmaker Harvey Hubbell V struggled with what was labeled a “perception problem,” and it made school a drag. His upbeat documentary Dislecksia: The Movie traces breakthroughs in the understanding and treatment of dyslexia, emphasizing that it’s a “learning difference” and not a disorder — and one that affects as many as 35 million Americans. Playful and at times self-indulgent, Hubbell’s film is a work of advocacy journalism that aims to inspire parents and educators. After bowing in New York (Oct. 4) and Los Angeles (Oct. 11), it’s scheduled for nationwide screenings on Oct. 17, some with Q&As, in conjunction with National Dyslexia Awareness Month.

The Bottom Line: Sometimes indulging in cutesiness, this bright and cheery doc provides a capsule history of dyslexia’s dark ages and recent scientific/educational breakthroughs.

With Billy Bob Thornton, Stephen J. Cannell, Joe Pantoliano, David Boies

Director Harvey Hubbell V

Northern Light: Film Review

Using family home movies, old report cards and jokey film clips to vivid effect, Hubbell lays the groundwork for a nuts-and-bolts examination of changes over the decades in treatment and teaching techniques. In the present tense, however, the first-person aspect of his documentary can veer toward the cutesy, as in man-on-the-street interviews or a multitude of shots of Hubbell making the film.

Dislecksia (whose title refers to the phonetic approach to spelling that many dyslexic people use) concisely explains that some brains are wired in a way that makes written language difficult to interpret — a physiological phenomenon that was unknown until the relatively recent advent of the printed word.

Underscoring the idea that dyslexia need not be an impediment, Hubbell includes a roll call of accomplished individuals who have the condition, from poster child Albert Einstein to attorney David Boies to actor Joe Pantoliano. Billy Bob Thornton reveals that he learns his lines by having people read scripts to him, and uses paper and pencil when he’s writing his own screenplays. Despite being left back in school, Stephen J. Cannell considers dyslexia a gift that has made him the writer-producer he is. To underscore Cannell’s success, Hubbell includes an image of his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — an example of the way the director’s choices can be more distracting than helpful.

Moving away from the famous and successful, the film grows more focused. Hubbell offers sobering statistics on to the negative impact that dyslexia can have, and the ways that a learning difference can turn into a disability; 70 percent of the U.S. prison population is functionally illiterate.

He shows impassioned teachers working with kids, and touches on the ways that the new field of educational neuroscience is leading to improved classroom techniques for all students, not just those born with differently wired brains. In keeping with the optimistic view, Hubbell deploys bright graphic elements, used throughout the film, to summarize his call to action.